Liu Guosong : Tradition in Renewal

- Literature

- Oriental Art

- Joan Stanley-Baker

- 2002.9

- Pages 46-54

The story of Chinese painting goes a long way, and certainly through the six odd millennia we have records of painted signs and images on Neolithic pots and rock carvings. From line-carvings of humans and animals, brushed or scratched designs on pottery, stone cliffs and jades, to images cast into bronze vessels, Chinese art is replete with a stunning array and succession of animate motifs and styles. But painting on pliant fabric has had, of course, a notably shorter documented history, because the earliest surviving evidence remains the fairly late funerary images on silk that have been unearthed in the 20th century in the southwestern Warring States Kingdom of Chu dating from the 3rd century BCE. From this period however literary evidence has also survived discussing the art and craft of painting. Here focus is largely on portraits that must bring out the inner life and individual spirit of the sitter.

Be the subject animals, animate symbols or human portraits, the single concept that underlies all such visual manifestation has been nothing other than life or, we might say, the evocation, the re-experiencing of powerful living energy. Little in early Chinese imagery was ever purely ornamental, and up to the Warring States period it was abstractions from the animal kingdom that had dominated the imagination, whilst plant-life remained virtually absent from the visual storehouse for the first four millennia.

What obsesses the Chinese mind has always been life and its myriad forms and formidable processes, including the power of activating the animate beings in inanimate painting form – even from the dead if need be.1 We have a hint of this from the Chuci (Songs of the South), which speak of recalling the two aspects of the departed soul. For, to the ancient Chinese, the dead were hardly devoid of animate spirit. These unseen ancestral spirits like those of celestial and earthly energies were most keenly felt, and were experienced as ever present. The goal of society was to communicate with these unseen but prevailing, dynamic forces, and to provide for them properly in order that they in turn may provide for us.

From this compulsion to communicate directly and effectively with this unseen but remarkably immediate world, the Chinese mind has for millennia focused on evoking, summoning life into the very venue of communication: painting or calligraphy. And that mission has indeed been accomplished to a remarkable degree. In fact, what distinguishes Chinese painting and calligraphy is this singular sense of life that charges the works. Calligraphy is sheer life through energies in motion that are registered as traces on silk or paper, where time and rhythm in shifting space are main ingredients. This is true also of Chinese painting, the single fixed factor of which is the freedom from fixed views that charge the work with internal movement and fluidity.

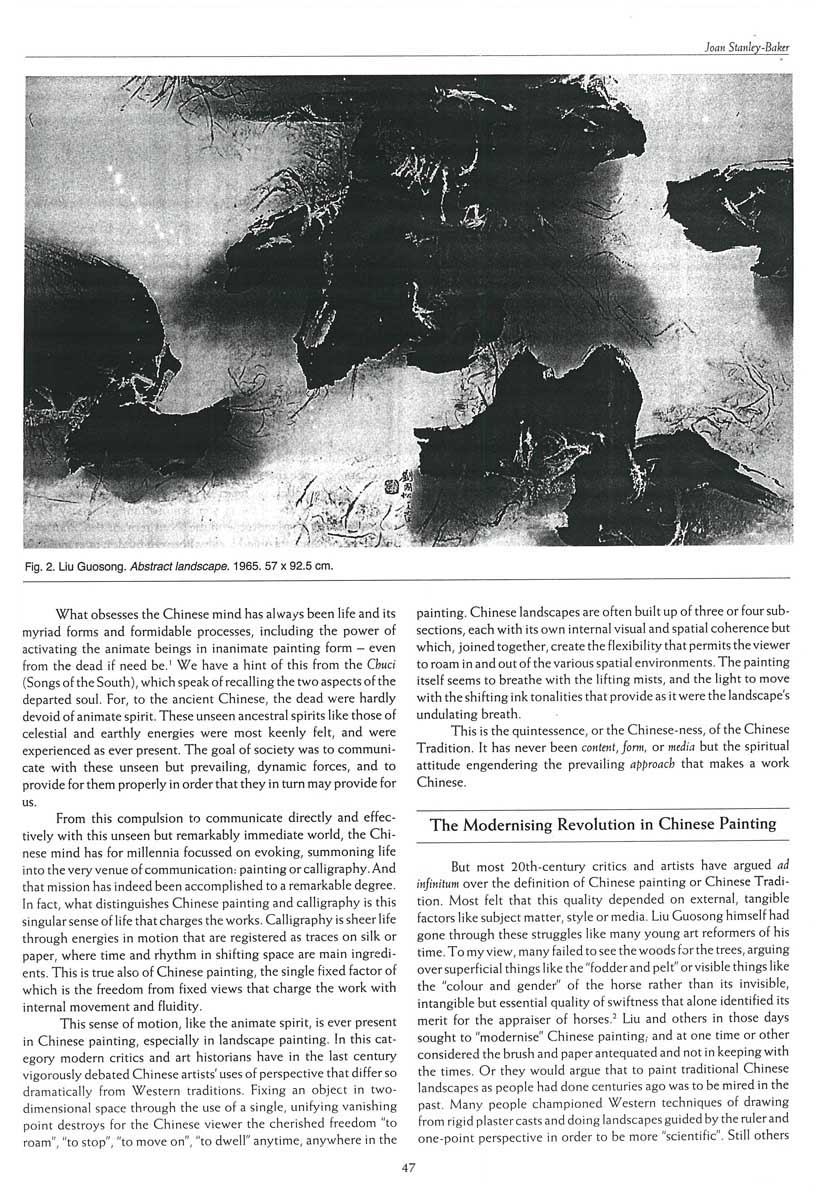

This sense of motion, like the animate spirit, is ever present in Chinese painting, especially in landscape painting. In this category modern critics and art historians have in the last century vigorously debated Chinese artists’ uses of perspective that differ so dramatically from Western traditions. Fixing an object in two-dimensional space through the use of single, unifying vanishing point destroys for the Chinese viewer the cherished freedom “to roam”, “to stop”, “to move on”, “to dwell” anytime, anywhere in the painting. Chinese landscapes are often built up of three or four subsections, each with its own internal visual and spatial coherence but which, joined together, create the flexibility that permits the viewer to roam in and out of the various spatial environments. The painting itself seems to breathe with the lifting mists, and the light to move with the shifting ink tonalities that provide as it were the landscape’s undulating breath.

This is the quintessence, or the Chinese-ness, of the Chinese Tradition. It has never been content, form, or media but the spiritual attitude engendering the prevailing approach that makes a work Chinese.

The Modernising Revolution in Chinese Painting

But most 20th- century critics and artists have argued ad infinitum over the definition of Chinese painting or Chinese Tradition. Most felt that this quality depended on external, tangible factors like subject matter, style or media. Liu Guosong himself had gone through these struggles like many young art reformers of his time. To my view, many failed to see the woods for the trees, arguing over superficial things like the “fodder and pelt” or visible things like the “colour and gender” of the horse rather than its invisible, intangible but essential quality of swiftness that alone identified its merit for the appraiser of horses.2 Liu and others in those days sough to “modernise” Chinese painting; and at one time or other considered the brush and paper antequated and not in keeping with the times. Or they would argue that to paint traditional Chinese landscapes as people had done centuries ago was to be mired in the past. Many people championed Western techniques of drawing from rigid plaster casts and doing landscapes guided by the ruler and one-point perspective in order to be more “scientific”. Still others argued that using the more Western media of watercolours, oils or acrylics would bring Chinese painting on a par with the world – that by speaking “Western languages” in paintings they would become more international.

In the minds of these reformers, much confusion was caused by their identification of subject matter or medium with “backwardness” or “modernness”. This was probably part of a period of narrow-mindedness caused by the lack of understanding of Western art in general and of Chinese art in particular. The spiritual poverty had sunk to such a depth that, already n the late 19th and 20th centuries Chinese “thinkers” were considering giving up their millennia strong heritage in order to “become more contemporary” (read more Westernised). In their minds to be Western was to be Modern (read Better). To be Chinese meant to them being backward, embarrassing, and undesirable. In the infamous May Fourth Movement, Dr. Hu Shizhi, instigated the abolition of the centuries-old Chinese literary style, the classical wenyanwen, from all schoolbooks, thus separating in one fell swoop all “modern” Chinese from their literary heritage, creating an unbridgeable gulf between all those born after the 1930s and their 2500-year heritage. Yet it had been this invisible, immaterial but spiritually essential legacy that had enriched the Chinese mind, and should perhaps have been the birthright of modern Chinese schoolchildren. With the “modernizing revolution”, by reading and writing in the vernacular and disregarding the literary prose of past centuries, some 20th Chinese “reformers” had undermined Chinese Tradition.

Traditional Visual Arts

Fortunately, the literary modernisation did not destroy for us the beauty of ancient painting and calligraphy. But when it came to creating Chinese painting and calligraphy in this century of cultural reform, opinions were bitterly divided between those who clung to Tradition and those who sought Modernisation because the latter, they thought, would provide equity for China with the West. Traditionalists insisted on learning by rote as they themselves had been taught. Since the 19th century when printed books came out with woodcut models of “styles of schools”, the mater-pupil relation had become one of the master demonstrating “the way” to do a tree, rock, bird or landscape in the “Northern” or the “Southern” mode, and the pupil copied line by line, dot by dot, over and over again till he could reproduce it from memory. This process precludes creative innovation, since any deviation from the model means failure to “grasp the method”.

The passive production of close-copies was now of course untenable as it was futile. Taiwan’s natural environment was quite different from that of Mainland China. Its political, social and cultural climate following 50 years of Japanese occupation was nothing that Qing painters could have imagined. Painters then were no longer leisured gentlemen of means who contemplate the timelss peace of a universe in its self-transforming internal dynamics. They were instead people who had use of the telephone, bicycle and even automobiles, wore Western clothes, carried fountain pens in their pockets, and anti-Manchu or anti-Japanese passions in their hearts. They had no time or intention to sit by mountain streams to admire rising mists. But to consider the other extreme, simply to go all-Western and throw out brush, ink and paper – was equally absurd. For art that does not directly reflect its own culture and times is not genuine art, more likely second-hand and fake. We saw it in Japan 40 years go in its desperate attempt to appear Western, down to its soul (its artistic manifestation), but like the business suits and briefcases, cars and boast that made Japan “modern” – all that was surface, but not the soul. The spirit of Japanese artists who speak only Japanese, then as now, remains Japanese, and any art that does not reflect that inimitable Japanese quality and could be mistaken for American or European art – is of course meaningless. Yet countless schools and galleries promoted just this type of second-hand copy work. The Japanese consciousness wished to be seen “to be on a par with Modern Western States” and adopted Western ways – down to Western art, which is the mirror of the soul and not the mark of one’s modernity!

Cultural Self-Identity Versus Foreign Concepts

The same drastic situation dominates the art of Taiwan today, where the most “avant-garde” manifestations are patent imitations of Western ideas, third-hand variations of forms and messages that had been triggered in their origins by a Western society as a reflection of its own special social, political or economic conditions of the time. Such derivative works copied from styles and expressions that had long become “established” (and soon passé) in the West, look pathetic when replayed in the Far East. For not only are they déjà vu, they are often, the artistic response without the triggering social ingredient, or Dong Shi imitating the favour-winning gestures of Xi Shi3 – a thing without generating basis, a form without meaning. That, too, is not creation. It is no less imitative than copying traditional Chinese masters’ sketch notes.

Surely Chinese artists are good for something better than Copying East or West!? Surely, with some reflection and experimentation, Chinese artists, too, can be creative, originators of art and art forms as they had proven brilliantly to be in the past millennia?

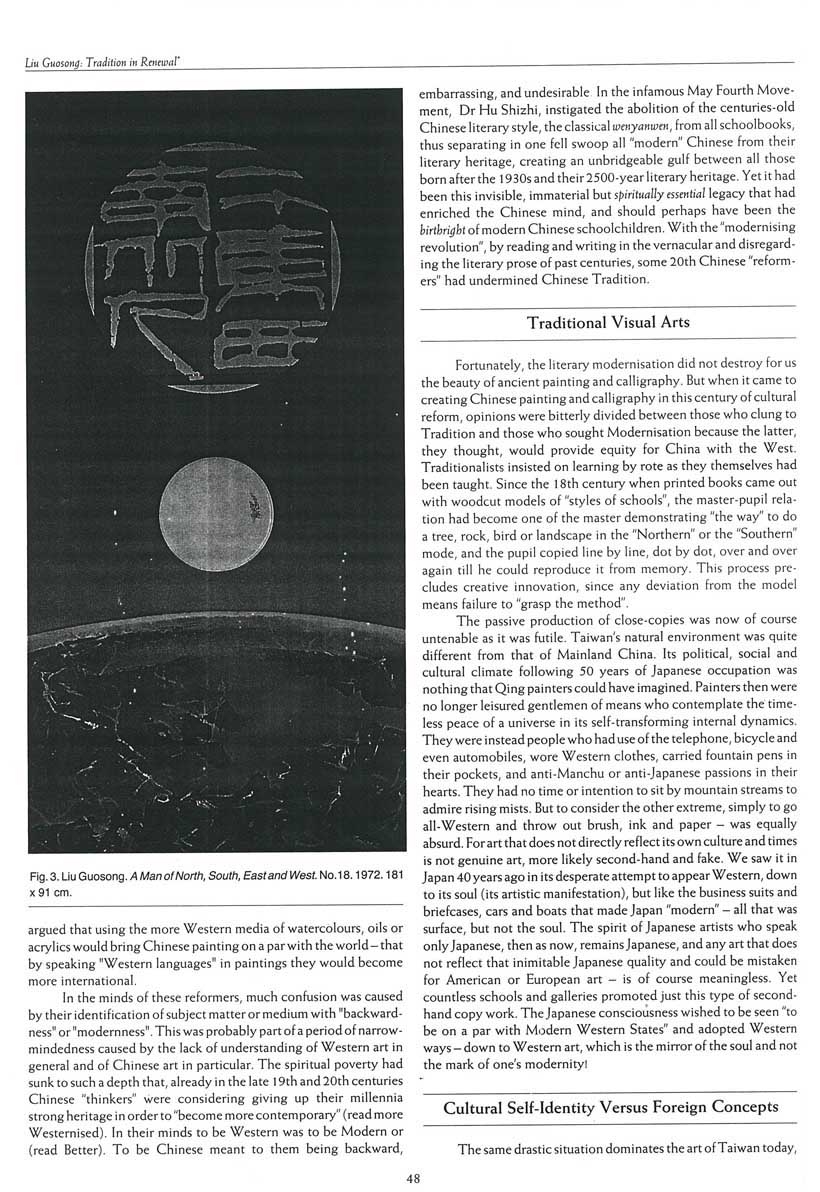

During the 1960s,when the intelligentsia of post-retrocession Taiwan once more found themselves engulfed in this crisis of cultural identity, the same dichotomy emerged on whether to copy the ancients of the West, Advocates of a New Art Form once more rose up to throw out brush and ink in favour of oils and canvas. This is when Liu Guosong (b. 1932) and others agonized over the issue of identity, tradition and survival.

At the heart of the dilemma was a basic question that curiously had remained unasked. It is simply this: “What (art) is it that Chinese people can do best (that others cannot equal)?” Of course, it is things that are born of the specifics of the Chinese way of life, and entirely reflective of Chinese cultural particulars. For no other culture today can equal the uninterrupted history of cultural continuity and development of the Chinese. Most societies surviving today have had to start over from scratch at one time or another following conquest or cultural domination from the outside. The Chinese while politically conquered and territorially dominated, remained ever the conquerors in the cultural sphere, where all invaders became sinicised. Amazingly, the sheer perseverance of Chinese culture had always been overlooked by all reformers and modernisers.

The sensible approach to identity crises of any society is for that society to identify and understand, and then to acknowledge and honour its own Tradition. That is, first of all we must truly understand the special attributes of our own heritage. And this cannot be done without recourse to another culture of civilization against which we can make meaningful comparisons. Once we have mastered its essentials, our creative artists must bring it up to our own times. As foods now cooked in pressure cookers and electric steamers make traditional Chinese cooking modern, so would certain shifts in the technology of Chinese painting (or for that matter Chinese opera, Chinese literature or Chinese medicine) bring the Chinese Tradition up to date without losing its age-old power.

Liu Guosong in the end has done precisely that. Not only has he found the peculiar qualities that make a work “Chinese”, he has also fathomed what makes a work “modern”, and in combining both, through various phases of creative trials and successes, he has updated Chinese inkwash painting both by releasing formal content from prescribed norms, but also by releasing formal content from prescribed norms, but also by inventing myriad techniques with brush, papers and colours, opening up infinite formal possibilities. In his case he has chosen to base his creative works on abstraction. This is not only modern American, but has been traditional Chinese ever since admirers of calligraphy were captivated by its inherent sense of movement, weight, texture, and expression, 1,700 years ago. In other words, abstraction has been part of the Chinese consciousness long before the West had its first awakenings in its power and beauty.

Western Abstract Art and Notions of Chinese Calligraphy

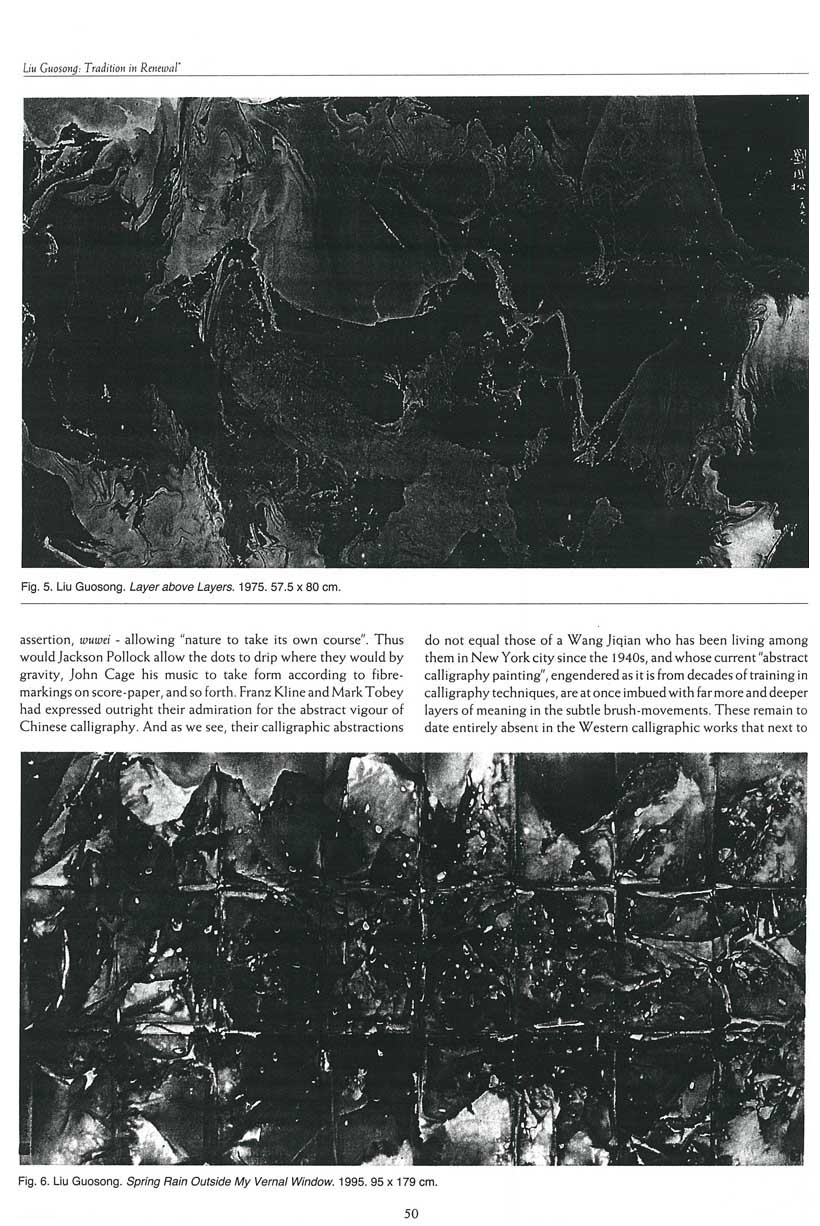

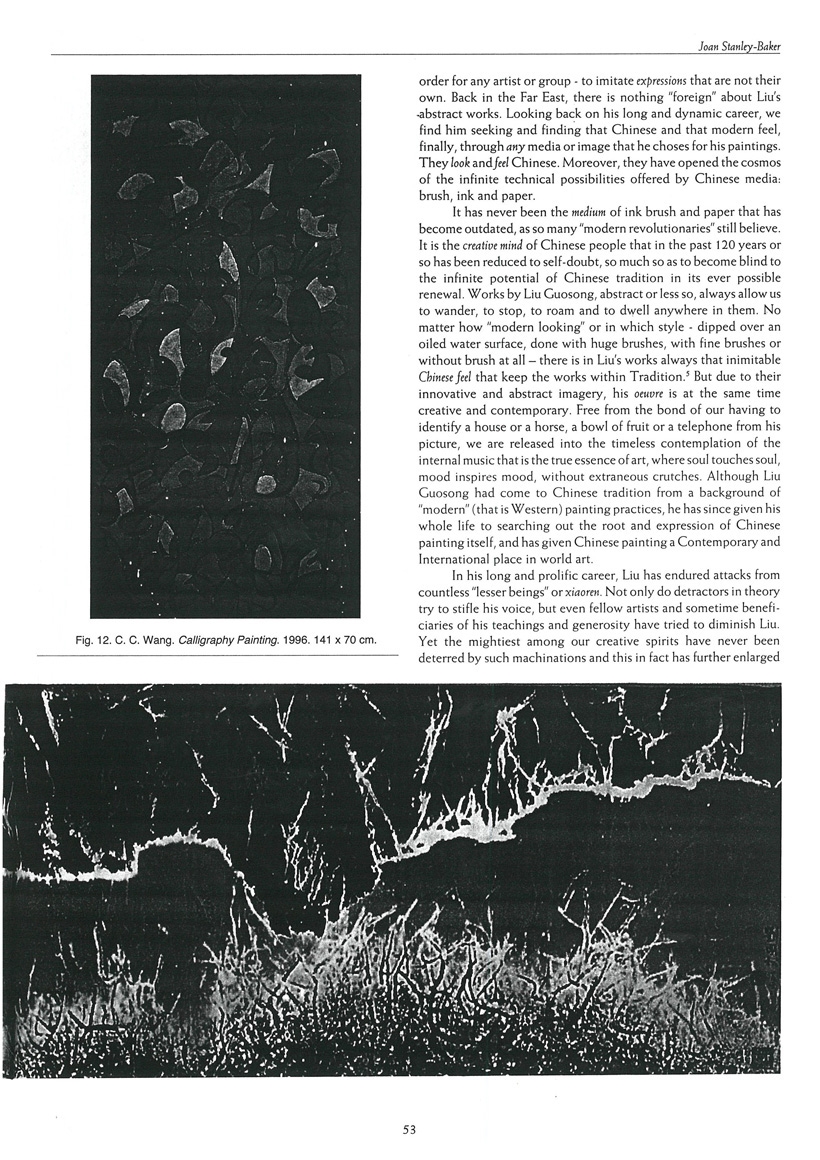

Although our recent generations have experienced “abstract art” primarily through the Abstract Expressionist movement that sprang up in New York during the post-depression years, those Jewish American immigrant artists themselves were under the influence of Chinese Daoist thinking, and experimenting with non-assertion, wuwei – allowing “nature to take its own course”. Thus would Jackson Pollock allow the dots to drip where they would by gravity, John Cage his music to take form according to fibre-markings on score-paper, and so forth. Franz Kline and Mark Tobey had expressed outright their admiration for the abstract vigour of Chinese calligraphy. And as we see, calligraphic abstractions do not equal those of a Wang Jiqian who has been living among them in New York city since the 1940s, and whose current “abstract calligraphy painting”, engendered as it is from decades of training in calligraphy techniques, are at once imbued with far more and deeper layers of meaning in the subtle brush-movements. These remain to date entirely absent in the Western calligraphic works that next to a C. C. Wang look crude and primitive.4

The Artistic Spirit

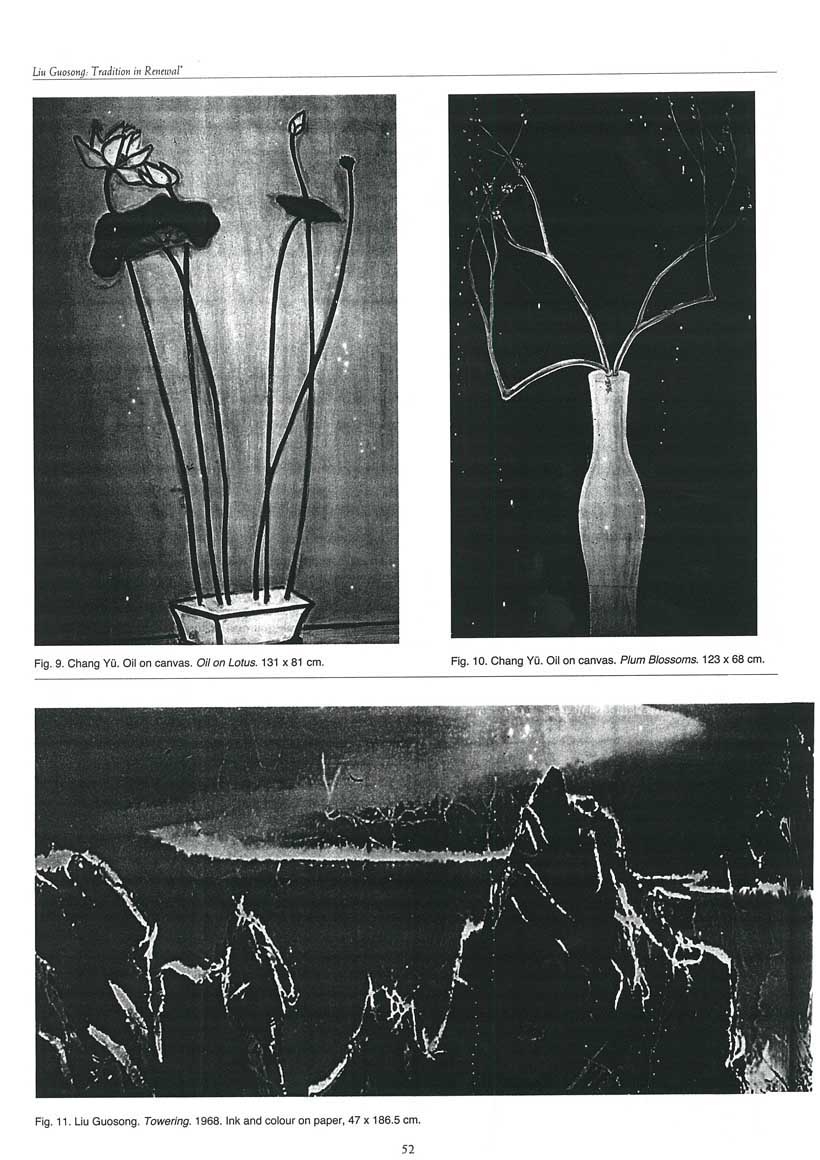

Renewal and Chineseness can both be engendered by using entirely foreign materials, and not only by traditional media (though these by habit can be sooner brought to greater advantage). This is demonstrated by the Taiwan artists resident in France, like Chu Dejun, whose hoary canvasses are enlivened with thick, unctuous oils in compelling colourist combinations that even “through the French tongue” impart a feel of Chinese landscapes and ancient, eternally Chinese emotions. Chu manages to create the spatial ambivalence that invites the viewer to roam and to dwell therein. While translucency of ink and colours provide ambivalence that give the sense of movement and change and emotionality to any painting, with adroit handling even dark rich opaque oils as in Chu Dejun’s large canvases, can by their formal relationships speak of change and movement. It is a step removed from the immediacy of translucent Chinese pigments, but it can be given a “Chinese feel” by a true master. Among the most poignant examples of a hauntingly Chinese expression, yet entirely Western in medium and content, are the elegiac paintings of the mater Chang Yu (1900-1966) who lived in Paris until he died during an excursion to Egypt. Chang’s works derive from Matisse and are yet entirely Chinese in their poetic lyricism.

And here Liu Guosong, like Chu, Chang, and Wang, is a Chinese master of 20th- and 21st century art, with an ability to produce the quintessential Chinese feel that is at the same time thoroughly “modern” and communicable on an international basis.

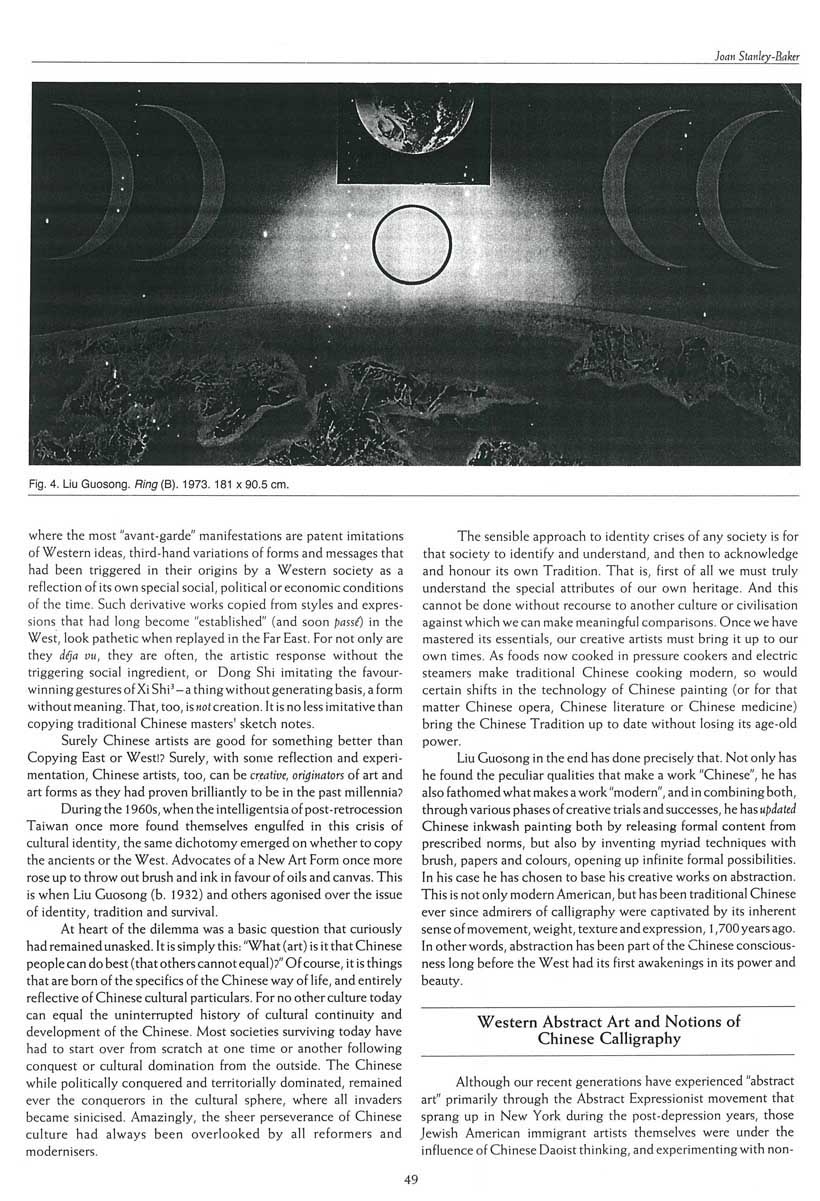

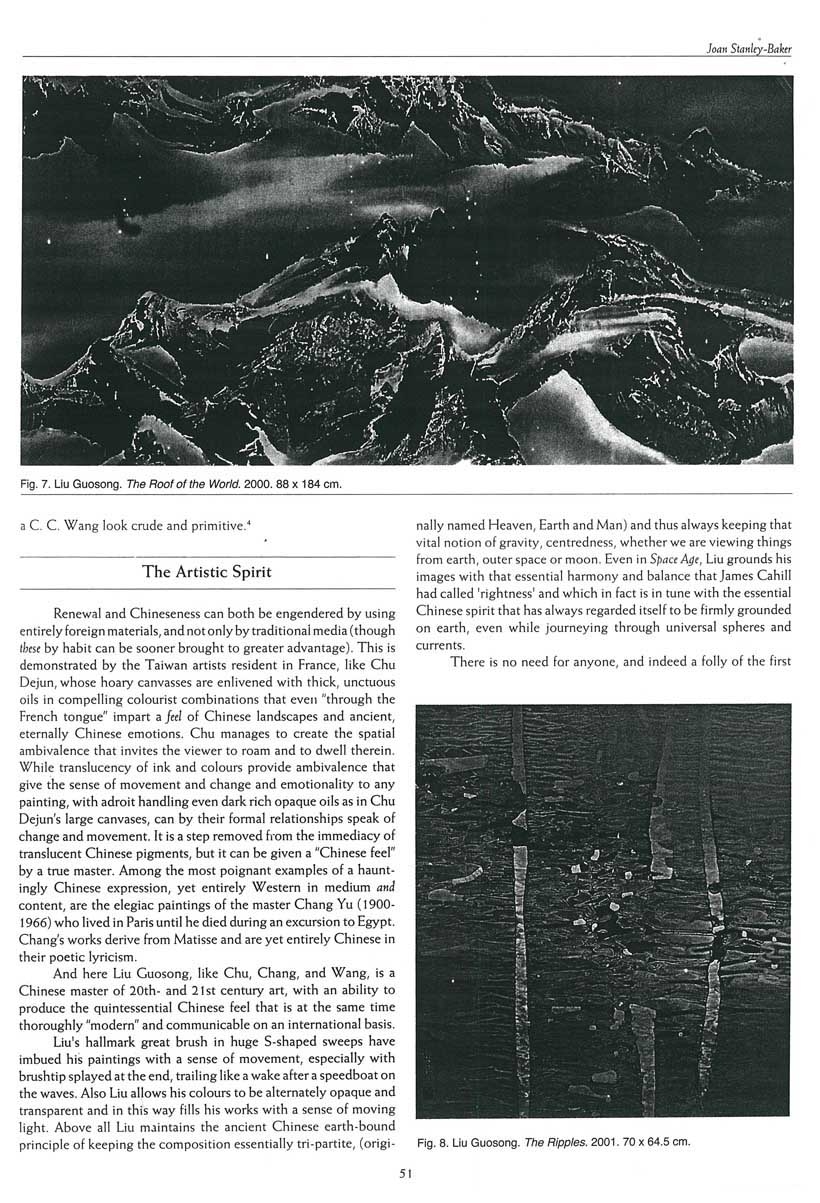

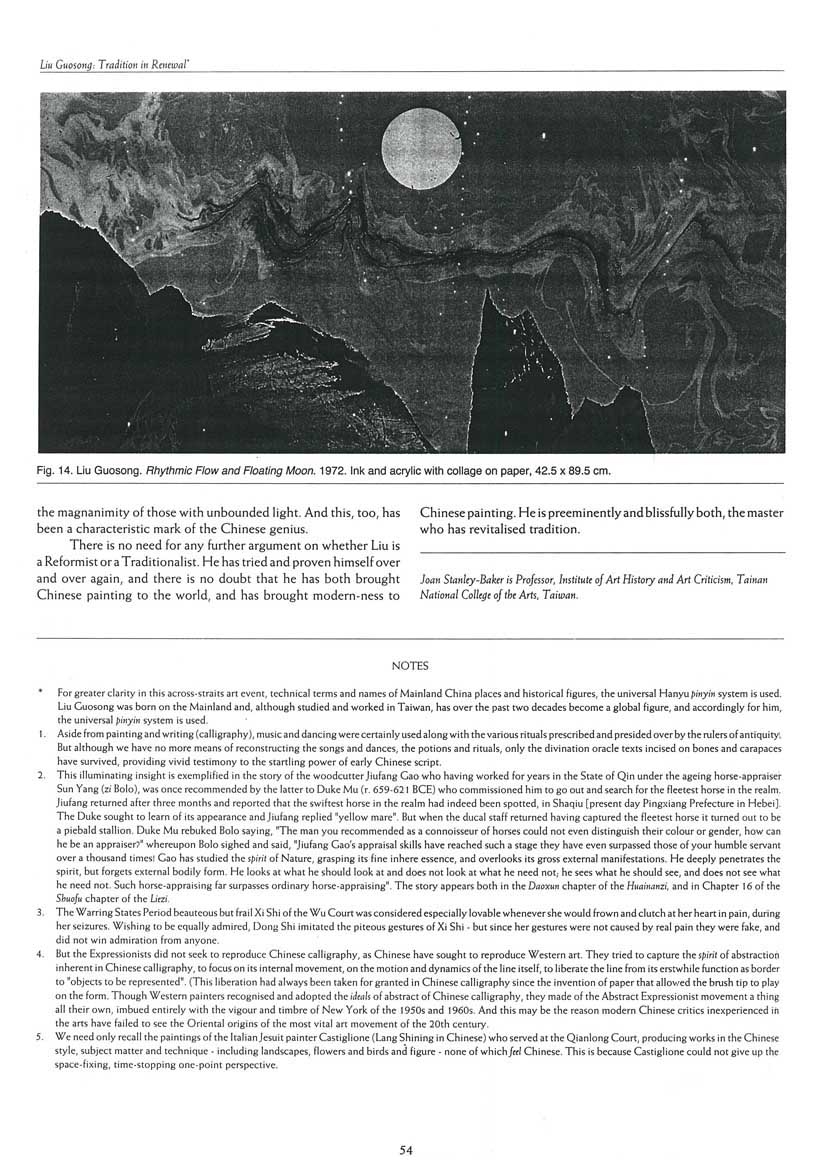

Liu’s hallmark great brush in huge S-shaped sweeps have imbued his paintings with a sense of movement, especially with brushtip splayed at the end, trailing like a wake after a speedboat on the waves. Also Liu allows his colours to be alternately opaque and transparent and in this way fills his works with a sense of moving light. Above all Liu maintains the ancient Chinese earth-bound principle of keeping the composition essential tri-partite, (originally named Heaven, Earth and Man) and thus always keeping that vital notion of gravity, centredness, whether we are viewing things from earth, outer space or moon. Even in Space Age, Liu grounds his images with that essential harmony and balance that James Cahill had called ‘rightness’ and which in fact is in tune with the essential Chinese spirit that has always regarded itself to be firmly grounded on earth, even while journeying through universal spheres and currents.

There is no need for anyone, and indeed a folly of the first order for any artist or group – to imitate expressions that are not their own. Back in the Far East, there is nothing “foreign” about Liu’s abstract works. Looking back on his long and dynamic career, we find him seeking and finding that Chinese and that modern feel, finally, through any media or image that he chooses for his paintings. They look and feel Chinese. Moreover, they have opened the cosmos of the infinite technical possibilities offered by Chinese media: brush, ink and paper.

It has never been the medium of ink brush and paper that has become outdated, as so many “modern revolutionaries” still believe. It is the creative mind of Chinese people that in the past 120 years or so has been reduced to self-doubt, so much so as to become blind to the infinite potential of Chinese tradition in its ever possible renewal. Works by Liu Guosong, abstract or less so, always allow us to wander, to stop, to roam and to dwell anywhere in them. No matter how “modern looking” or in which style – dipped over an oiled water surface, done with huge brushes, with fine brushes or without brush at all – there is in Liu’s works always that inimitable Chinese feel that keep the works within Tradition.5 But due to their innovative and abstract imagery, his oeuvre is at the same time creative and contemporary. Free from the bond of our having to identify a house or a horse, a bowl of fruit or a telephone from his picture, we are released into the timeless contemplation of the internal music that is the true essence of art, where soul touches soul, mood inspires mood, without extraneous crutches. Although Liu Guosong had come to Chinese tradition from a background of “modern” (that is Western) painting practices, he has since given his whole life to searching out the root and expression of Chinese painting itself, and has given Chinese painting a Contemporary and International place in world art.

in his long and prolific career, Liu has endured attacks from countless “lesser beings” or xiaoren. Not only do detractors in theory try to stifle his voice, but even fellow artists and sometimes beneficiaries of his teachings and generosity have tried to diminish Liu. Yet the mightiest among out creative spirits have never been deterred by such machinations and this in fact has further enlarged the magnanimity of those with unbounded light. And this, too, has been a characteristic mark of the Chinese genius.

There is no need for any further argument on whether Liu is a Reformist of a Traditionalist. He has tried and proven himself over and over again, and there is no doubt that he has both brought Chinese painting to the world, and has brought modern-ness to Chinese painting. He is preeminently and blissfully both, the master who has revitalized tradition.

Joan Stanley-Baker is a professor at the Institute of Art History and Art Criticism, Tainan National College of the Arts, Taiwan.

NOTES

*For greater clarity in this across-straits art event, technical terms and names of Mainland China places and historical figures, the universal Hanyu pinyin system is used. Liu Guosong was born on the Mainland and, although studied and worked in Taiwan, has over the past two decades become a global figure, and accordingly for him, the universal pinyin system is used.

1.Aside from painting and writing (calligraphy), music and dancing were certainly used along with the various rituals prescribed and presided over by the rulers of antiquity. But although we have no more means of reconstructing the songs and dances, the potions and rituals, only the divination oracle texts incised on bones and carapaces have survived, providing vivid testimony to startling power of early Chinese script.

2.This illuminating insight is exemplified in the story of the woodcutter Jiufang Gao who having worked for years in the State of Qin under the ageing horse-appraiser Sun Yang (zi Bolo), was once recommended by the latter to Duke Mu (r. 659-621 BCE) who commissioned him to go out and search for the fleetest horse in the realm. Jiufang returned after three months and reported that the swiftest horse in the realm had indeed been spotted, in Shaqiu [present day Pingxiang Prefecture in Hebei]. The Duke sought to learn of its appearance and Jiufang replied “yellow mare”. But when the ducal staff returned having captured the fleetest horse it turned out to be a piebald stallion. Duke Mu rebuked Bolo saying, “The man you recommended as a connoisseur of horses could not even distinguish their colour or gender, how can he be an appraiser?” whereupon Bolo sighed and said, “Jiufang Gao’s appraisal skills have reached such a stage they have even surpassed those of your humble servant over a thousand times! Gao has studied the spirit of Nature, grasping its fine inhere essence, and overlooks its gross external manifestations. He deeply penetrates the spirit, but forgets external bodily form. He looks at what he should look at and does not look at what he need not, he sees what he should see, and does not see what he need not. Such horse-appraising far surpasses ordinary horse-appraising”. The story appears both in the Daoxun chapter of the Huainanzi, and in Chapter 16 of the Shuofu chapter of the Liezi.

3.The Warring States Period beauteous but frail Xi Shi of the Wu Court was considered especially lovable whenever she would frown and clutch at her heart in pain, during her seizures. Wishing to be equally admired, Dong Shi imitated the piteous gestures of Xi Shi – but since her gestures were not caused by real pain they were fake, and did not win admiration from anyone.

4.But the Expressionists did not seek to reproduce Chinese calligraphy, as Chinese have sought to reproduce Western art. They tried to capture the spirit of abstraction inherent in Chinese calligraphy, to focus on its internal movement, on the motion and dynamics of the line itself, to liberate the line from its erstwhile function as border to “objects to be represented”. (This liberation had always been taken for granted in Chinese calligraphy since the invention of paper that allowed the brush tip to play on the form. Though Western painters recognized and adopted the ideals of abstract of Chinese calligraphy, they made of the Abstract Expressionist movement a thing all their own, imbued entirely with the vigour and timbre of New York of the 1950s and 1960s. And this may be the reason modern Chinese critics inexperienced in the arts have failed to see the Oriental origins of the most vital art movement of the 20th century.

5.We need only recall the paintings of the Italian Jesuit painter Castiglione (Lang Shining in Chinese) who served at the Qianlong court, producing works in the Chinese style, subject matter and technique – including landscapes, flowers and birds and figure – none of which feel Chinese. This is because Castiglione could not give up the space-fixing, time-stopping one-point perspective.