Making Of A Modern Chinese Painter

- Literature

- The China News

- Linda Wu

- 1969.10

The magnificent young man with a brush - this is Liu Kuo-sung. China’s contribution to the contemporary art world. His one-man-show at the National Gallery of Art which opened last Sunday is perhaps the most exciting exhibition of its nature to come to Taipei this year.

Winner of the US$1,000 Award for Painting in “Mainstreams ‘69” at the Second Marietta College International Competition Exhibition for Painting and Sculpture, Liu first stormed the art world in the States as early as 1965 when ten of his works toured the country in an exhibition titled “The New Chinese Landscape.” This was organized by Dr. Li Chu-tsing and Thomas Lawton under a grant given by The John D. Rockefeller 3rd Fund.

His works won such wide acclaim from the American critics and art lovers that a number of one-man-shows were immediately arranged especially for him. This in turn led to a contract with the famed Lee Nordness Galleries in New York to handle all his works outside of Taiwan and a JDR 3rd Fund award which allowed him to travel for two years around the world visiting museums, art schools, galleries, and private collections.

One Of Very Few

The name Liu Kuo-sung to many who have seen his works evokes abstract expressionistic paintings of dynamic, evermoving, clear sweeping brush strokes which by their simplicity beauty, and sheer force have attracted thousands of admirers for the artist. But what is unique about Liu is not so much his rising international reputation as his ability to grasp both the ideals of China’s rich art tradition and the meaning of our modern age. In this lies his greatness. He is one of the very few who have succeeded in blending together elements from both the old and the new and from both East and West.

This is quite evident in the 50 some paintings presently being shown. Though most of his best works are now owned by museums and art galleries, and private collectors in the States and Europe, the exhibition contains a number of excellent examples of the various stages of his development as an artist. They trace his career from his student days 17 years ago at the National Taiwan Normal University, where he was required to study both Chinese and Western painting, up to the present, and reveal in part the hardships, struggles, experimentations, and soul searching which have gone into the making of an artist of Liu’s caliber.

From the changes in style and technique, we follow his rejection from traditional Chinese painting to his equally agonizing realization of the fallacy of his innovation in Western styles.

Assimilation

Dr. Li Chu-tsing, professor of art history at the University of Kansas and research curator of the Nelson Gallery of Art in Missouri, in his book, “Liu Kuo-sung: The Growth of a Modern Chinese Painter” feels, however, that this period of assimilation was vital to Liu’s development.

“Even without any direct contact with real modern masterpieces of the West, he had gone through almost a century of artistic experiences in Europe and America…

“This assimilation was also valuable in definitely liberating him from the restrictions of traditional paintings. Now he was a master not only in Chinese ink painting, but also one in watercolor, collage, plastered surface, dribbling methods, automatic painting, and other graphic means. He thus had a whole scope of possibilities to draw from.”

Three Periods

Liu’s experiences after this time could be divided into three periods: the first from 1959 to 1963 when he was experimenting with various styles trying earnestly to search for something which could be called his own.

“Initially, I firmly believed that the national character could be expressed only in spirit and not in materials and tools. In style and expression, I wanted to push the stagnant Chinese painting tradition forward and glorify it. Thus I began to use the canvas of Western painting as a vehicle for washes and splashes in ink.”

But something happened in 1961 which again changed the direction of his art. While an instructor in the architecture department of Chungyuan Christian College of Science and Engineering, he participated in a number of converations on the question of being true to the materials one was working with.

“They felt that in architecture, whatever materials one employed one must try to be true to materials. That is to say, one must utilize and develop them to the utmost in terms of their special characteristics and avoid using them for other materials, for to force characteristics other than their own on them is simply falseness and cheating.

“To me, this idea was true not only in architecture, but also in all forms of art. Thus I repeatedly asked myself: Are you also committing the same errors by using oil painting techniques to express the feeling of ink painting? Isn’t this also faulty and cheating? If you want to broaden and cultivate the domain of ink painting to develop it to a great tradition, why can’t you paint ink on paper instead of the more fashionable materials of oil painting? Through repeated self-questioning, I finally decided to give up oil painting techniques and started working in ink on paper. That took place toward the end of 1961.”

The result of this redirection can be seen in his two scrolls titled, “Ink Wit.” From hence, Liu was to enter his most exciting period up to the present.

John Canady, art editor of The New York Times, once wrote “…Liu Kuo-sung is at any rate a dashing exponent of traditional Chinese landscape painting hybridized with modern abstraction.

“His apparently broom-sized brush, filled with ink or color, charges around the field of the paper with great vigor; seas, mountains, and valleys appear and disappear within the pattern; here and there the paper seems to have been rent by the weights and forces that open up chasms – but it is only collage. And all the while, everything is very elegant.”

Breakthrough

This is perhaps typical of the comments made by critics and art lovers all over the world about Liu’s works during this exciting period of his development. The years between 1963 and the 1968 were vital to his being ranked among the most distinguished artists of modern China. He had finally made a breakthrough.

His return to the use of Chinese ink and paper as discussed in yesterday’s installment and his successful experimentation with a type of “mien” paper which was rougher in texture than that ordinarily used were vital to his developing a style which he could call his own.

“I began painting on the rough surface of the paper with large ink brushes and then pulling out the heavy streaks of cotton fibres from the painted areas, thus leaving white streaks within the dark patches.” This technique was extremely effective and gave Liu the tool to create a whole stream of new and exciting works.

“Fantasy in February,” now in the Mrs. Rose Cooper collection in Detroit, was one of the most exciting works to come from his studio during this time. According to Dr. Li Chu-tsing, the painting reflects in part Liu’s confidence in his free and sure way of handling his brush and ink. Compared with his earlier works in which both his ink and brush work are more controlled and the forms more tradition-oriented, this painting reveals an outburst of spontaneous energy, giving free reign to his imagination.

“Yet these free plays of ink still evoke images like before…Here they seem to be ever changing and evolving. In addition…as a counterpoint to the dark strokes and patches, a number of light lines and soft grays appear on the left side, created by a greater exploration of the potentials of the fibres on the cotton paper.

“Such a contrast between these two kidns of tonal qualities of ink and of texture have become a typical feature of Liu’s works from then on – a contrast which creates a heightened sense of visual drama.”

Into The Depth

His compositions are never centralized, nor are they ever in verticals or horizontals; they are rather for the most part off-centered curving and turning inviting the viewer to move into the depth of the picture, into the world he has created.

In 1966, Liu won a grant from the JDR 3rd Fund which allowed him to spend a year in the States and to travel extensively in Europe. This opportunity not only opened his eyes to the great European heritage but also allowed him to study firsthand the more recent developments in European and American paintings.

But contrary to popular beliefs about people who go abroad, Liu did not show any major redirection in his style. Rather the trip abroad heightened his own nationalistic attitudes and helped him to deepen his art in all respects: technically, stylistically, and conceptually. The result according to all who have noted the changes was a greater enrichment of his art.

The year 1967 saw the beginning of another period in his development. Op Art and the dramatic Apollo moon landing brought to his painting an exciting change – a change not so much in style as in composition. While the lower part of the painting is given much the same treatment of landscape-like abstraction, the upper part is now covered with a big collage in either round or square form.

As explained by Liu, this new connection between his painting and space explorations not really strange, for his painting and space explorations not really strange, for hi works have always shown some semi-abstract shapes suggestive of mountains and seas of clouds viewed from above.

“This is something which can be traced back to tradition. Chinese painters from the Sun Dynasty on down, if not earlier, have always painted views seen from an imaginary high point in the clouds…”

“There is almost an obsession in looking at things from a far and high spot above as a means of transcending all the pettiness of this dusty world and of achieving an identity with the great universal spirit.

Fascinations of Space

“It is not surprising then that space exploration should become attractive to Chinese painters, for the fascinations of space could become extensions of their own desire to transcend their earthly desires.”

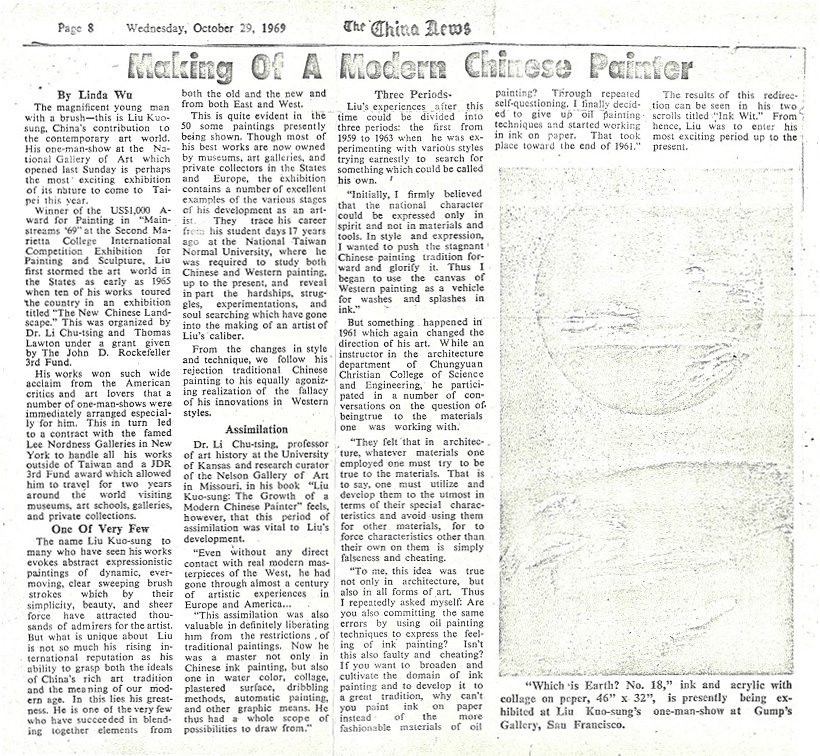

Composition-wise the round globe has brought new life to his paintings. Together, the broad sweeping, free and irregular forms which were typical of his works in the past and the new controlled hardedge sphere create a tendentious relationship, each enriching the feeling of the other. This is especially true in his series titled “Which is Earth?”

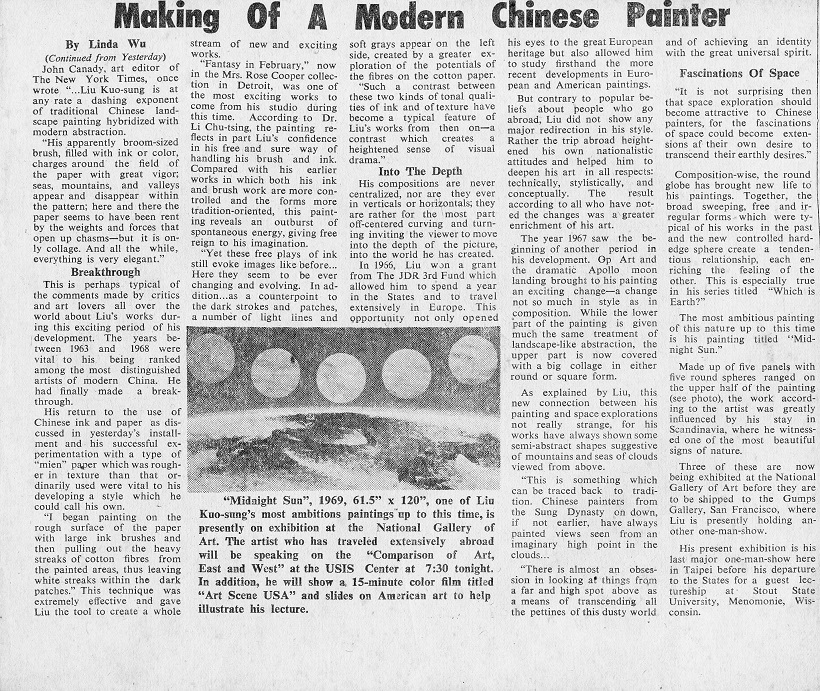

The most ambitious painting of this nature up to this time is his painting titled “Midnigh Sun.”

Made up of five panels with five round spheres ranged on the upper half of the painting, the work according to the artist was greatly influenced by his stay in Scandinavia, where he witnessed one of the most beautiful signs of nature.

Three of these are now being exhibited at the National Gallery of Art before they are to be shipped to the Gumps Gallery, San Francisco, where Liu is presently holding another one-man show.

His present exhibition is his last major one-man-show here in Taipei before his departure to the States for a guest lectureship at Stout State University, Menomonie, Wisconsin.