The Art of Liu Kuo-sung

- Literature

- “LIU KUO-SUNG”

- Pages 8-9

- 1992.2

- Micheal Sullivan

It is a pleasure to me to write a few words about the art of Liu Kuo-sung, whose career as a leading painter in Taiwan I have been following for nearly twenty years. When we first met in Taipei, he was a prominent member of a gallant little band of artists who called themselves the Fifth Moon (or May) Group, dedicated to creating a movement that was both Chinese and contemporary. Valiantly they struggled against the obscurantists who condemned their painting as unChinese, unpatriotic, even - because they admired Picasso - tainted with communism.

Liu Kuo-sung won his battle partly because the Group attracted so much attention abroad, and thus put Taiwan on the map of contemporary world art. In the ‘sixties, the era of Pop, Op, Funk, Junk, and Minimal art, painting that was both contemporary in feeling and beautiful to look at was, not only in Taiwan but throughout the Western world, rare indeed.

The Taiwan movement reached out to join hands with the pioneers of contemporary art in Hong Kong. Long ignored or even condemned in the People’s Republic, the work of Liu and his fellow painters finally achieved its overdue recognition in 1983 and 1984 with exhibitions in China that were received, at least by the artists, with great enthusiasm. There painters, because they were themselves Chinese, have played a key role in enlarging the boundaries of what is acceptable in contemporary art in China today, and, with the writings of Wu Guan-zhoung, in persuading the faint-hearted not to be afraid of Abstraction. So today, no defence of Liu Kuo-sung is necessary, even in Peking. Instead, I would like to glance back over the past twenty years of his career to chart his course.

When Liu Kuo-sung first made his breakthrough into Abstract (or almost Abstract) Expressionism, it was undeniably under the influence of modern Western art - the liberating force for so many Far Eastern painters. But, being Chinese, he was not content, as some Japanese artists have been, brilliantly to copy the style of, say, Sam Francis or Franz Kline. He had to think it through, to reach back into his own tradition to find a reason to be painting, as a Chinese, in that particular way. As had Zao Wou-ki a little earlier in Paris, he found the roots of Abstraction in the Chinese calligraphic gesture which was never an exercise in pure form, but always had meaning beyond the form. On a philosophical level, that gesture is an expression of the vital reverberations of the cosmos itself. However abstract Liu’s ink painting might appear, contact with nature was never lost.

By 1968 it might have seemed that Liu Kuo-sung had explored this vein as far as it could go, exploiting not only the possibilities of the expressive brushstroke, but floating the ink on the surface, painting on the back of the paper, using the very texture of the paper itself, pulling out the coarse fibres here and there so that tremulous shimmering threads like little bursts of electric charges seem to dart in and out among the rocks. These works were both vibrating with life and beautiful texture.

Then suddenly Liu Kuo-sung’s painting took a new direction with the Which is Earth? Series which was to occupy him for the next five years. Here the obvious inspiration was the Apollo missions and the wondrous discovery of the Earth from space; a less obvious inspiration is said to be the huge globular lanterns that hang from the eaves of Chinese temple roofs. These works were a spectacular success, generally saved from any taint of self-consciousness or cleverness by Liu’s marvellous handling of the style he had created. A brilliant idea can be pushed just so far, and by 1974 Liu Kuo-sung seems to have decided that he had pushed it far enough.

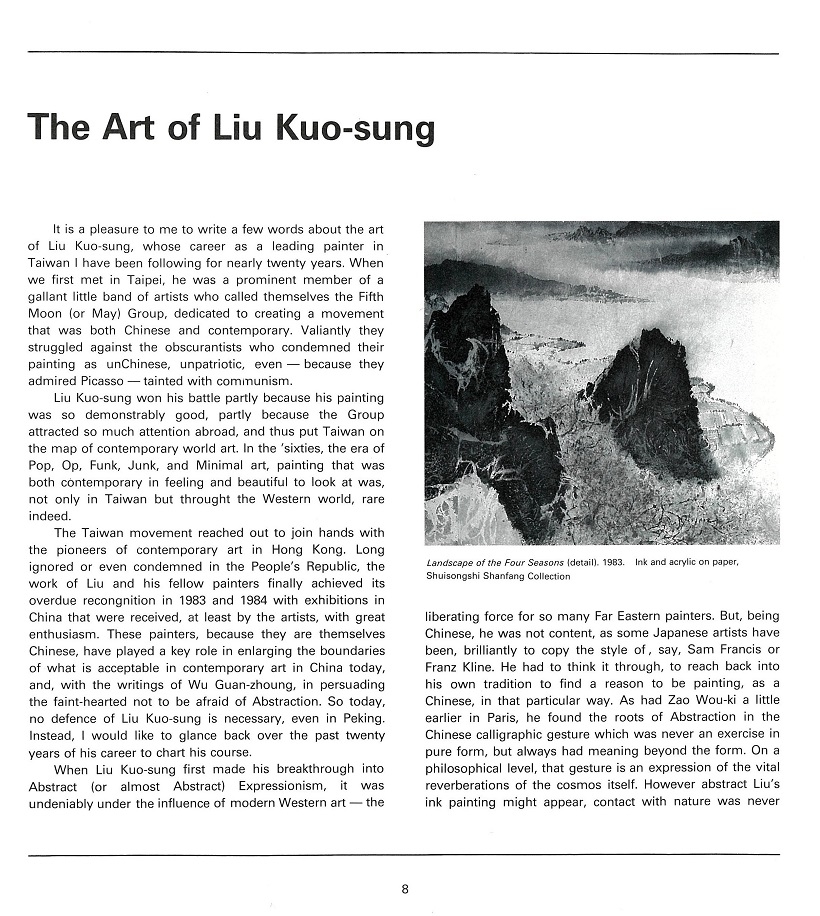

By then, the moon was already drifting back into deep space, and by the following year had vanished altogether. Liu had said what he wanted to say with great skill and now moved - both forward and back. If here and there a reference to the cosmos appears, as in And the Earth was without Form and Void of 1985, we are reminded of those craggy, improbable, shapeless asteroids that wander in space and circle around the planet Venus. These references apart, Liu Kuo-sung has come back to earth; in fact, it might not be too much to say that he is actually discovering it for the first time since he became a mature painter. His beautiful paintings of the mid-eighties are undeniably landscapes. All that he had learned about form and texture in the earlier works is here, but now we find, rather astonishingly, echoes of the archaic style of the T’ang Dynasty in A Hymn to Blue Green Landscape (1984-85), and a more consistent reference to the monumentality of Northern Sung in High Landscape (1984), One Atop the Other (1983), and - the most interesting of all - which too suggests Northern Sung, a realism that conjures up precipitous mountains, glaciers, waterfalls. All this rediscovery of nature is brought together in the spectacular Landscape of the Four Seasons, a work of great energy and changing mood, that range from the lyrical opening through the almost too tempestuous summer and autumn to the glacial silence and grandeur of winter. The scroll ends with such chilling finality that one is tempted to join the end in a complete circle with the beginning, or to search in the snow for the red plum blossom that is the first herald of the coming Spring.

From all of Liu Kuo-sung’s work so far one thing has been absent - man himself. Is he about to make his first shy appearance? For the first time evidence that Liu’s world is inhabitable (although still for the most part rather inhospitable!) appears in his arctic landscapes - I am thinking particularly of Mountain Light Blown into Wrinkles (1985), in which it is just possible to imagine the tiny figure of a fur-clad traveler with his sled and dog-team; while if we could swoop down close enough to the exquisitely-painted rice-fields in the Spring section of his Landscape of the Four Seasons scroll, we might just make out the farmers who are surely toiling there.

Have these new hints of the “liveable” landscape something to do with Liu Kuo-sung’s own travel in China and the warm reception he and his paintings received there? Or did his visits revive memories of his childhood in Shantung? I have not asked him and do not know. All I can say - and this is a tentative and very personal opinion - is that the hints here and there in his most recent work of a new synthesis of the representative and the abstract seem to point to immense possibilities for the future development of his art.